Ecocide demands a response.

The Dark Mountain Manifesto, 2009

This autumn we’ve begun an experiment in community-based education at Falmouth University. The idea grew from an End Fossil! student occupation of the main campus lecture theatre here in November 2022. Those eight occupiers – a good example of how our world is changed and changed again by a few people deciding to act together – subsequently reformed into a more extensive network called The People’s Assembly Community. Over the past year PAC have, in collaboration with the Student Union, organised a series of People’s Assemblies both on and off campus, a number of which formed the heart of local UCU strike teach-outs and drew gatherings of up to 80 at a time.

One of the occupiers’ demands was to see the ongoing obliteration of Earth’s life systems by the fossil fuel economy spoken to coherently and critically on our campuses. From the ensuing monthly PAs – and from weekly discussions about how we might best address this need – arose the emerging venture we’ve decided to call Ecological Citizenship.

The premise that we’re setting out from is familiar enough. Taken in the round, neither the collapse of Earth’s life systems under the impact of industrial consumer societies, nor the impending consequences of this collapse for human societies of any kind really confront us with a ‘problem’. Universities have a predisposition to frame the situation in such terms because one of the things an “existential crisis” fosters when construed as a problem is a thriving market in educational products promising to equip their students with the creative and intellectual skills to solve it. As Jonathon Rowson reminds us, crisis and solution to crisis has always been the lifeblood of industrial capitalism.

A School of Art, for instance, seen through this neoliberal lens, holds cultural value and relevance only insofar as it brings our combined creative talents to bear on innovating technological and economic market solutions to such ‘real world’ problems: challenging its student-customers to Get Real, as Falmouth’s previous Vice Chancellor was fond of putting it.

Get real indeed. The more accurate term for our rapidly worsening situation is of course a predicament. In this context the word’s sometimes underscored by qualifiers like wicked or super-wicked, but to my ear predicament still does the job: a situation before whose inescapable consequences there are simply no proportionate answers.

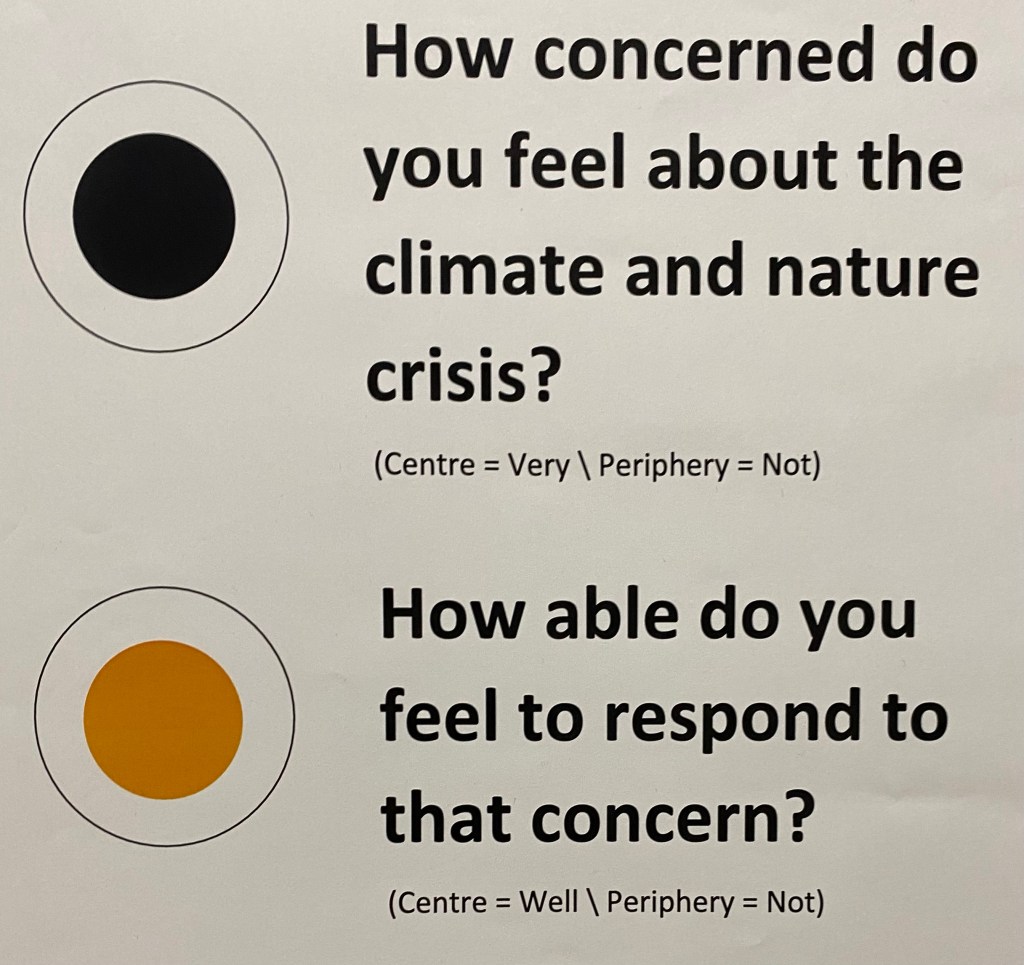

Faced with an acceleration towards socio-ecological collapse which governments and universities alike seem to have banally accepted as a regrettable externality to quarterly profits, conversations about hope and despair tend to be near at hand. I imagine holding space for such conversations will be a central part of our community’s ongoing work, but given its immediate context two other factors feel worth noting here at the outset.

The first is that if a predicament by definition offers us no way out, what it nonetheless requires is a response. If we turn to a School of Art, then, in search of congruent or illuminating responses to ecocide, we may find quite different conversations emerging than if we task it with fostering practical, economic or imaginal solutions. As if that had ever been the arts’ essential value in our shared lives.

The second factor was spoken of in depth some forty years ago by the American ecologist and educator David Orr. The climate and ecological crisis, Orr tells us, far from being solved by higher education, is in a very real sense being driven by our ballooning higher education economies. As Orr puts it, when you look for those holding positions of influence within the transnational networks overseeing global ecocide, what you tend to find is people with Degrees and PhDs. The intervening decades have proved Orr’s observations devastatingly true, as the minority world’s HE institutions have swelled and proliferated in close step with a biological annihilation whose pace and scale has more than doubled since he spoke about it, across all key rubrics.

Which leaves us in something of a bind as we come together within a university system that remains as committed as ever to serving and invigorating the runaway death project otherwise known as a globalised growth economy.

Perhaps Ecological Citizenship’s first principles, then, might include cultivating an ability to laugh from the soles of our feet at the vanity of our intentions, even as we set about realising them with patience, cunning and determination.

Leave a comment