Where else does this begin? Perhaps here, in April 2019. On a sunny morning in West London, where a few thousand of us fill the slow lane of the A4. It’s a month since this ‘March for Life’ set out from Land’s End, two months since a local Greenham Common veteran, Jackie Dash, first mooted her madcap plan in a small community café in Penryn.

I’ve hooked up with two Bristol friends to fall in with the final ten-mile leg of the marchers’ gruelling, triumphant slog from Cornwall to Hyde Park Corner. As our sprawling column drums its way along Hammersmith flyover, one of them talks about how it’s come as a shock to see so many of her fellow artists abandoning their work to be part of this uprising. These are people, she tells me, who she knows to be deeply committed to what they do, now quitting their studios to let this thing claim their whole attention. Once you see how important this is, she muses, how can you just go back to making art?

What happened that year feels from here like a kind of infection – a highly contagious Yes that outran all of us as it took hold in pub backrooms and draughty village halls, sweeping through local communities up and down the land. For every one of us they arrest four more will take our place. When they move to repress us we won’t back down, we’ll maintain nonviolent discipline. When others see this for what it is they’ll want to be part of it. Courage calls to courage everywhere.

I wonder sometimes what all those Bristol artists are up to now. My guess is most of them had quietly slipped back to their studios even before that heady year slammed into an actual pandemic. And good for them. This isn’t about taking a position. But that interrupted state which my friend spoke about as we crossed Hammersmith flyover has stayed with me in more senses than one, and six years on, it has a name.

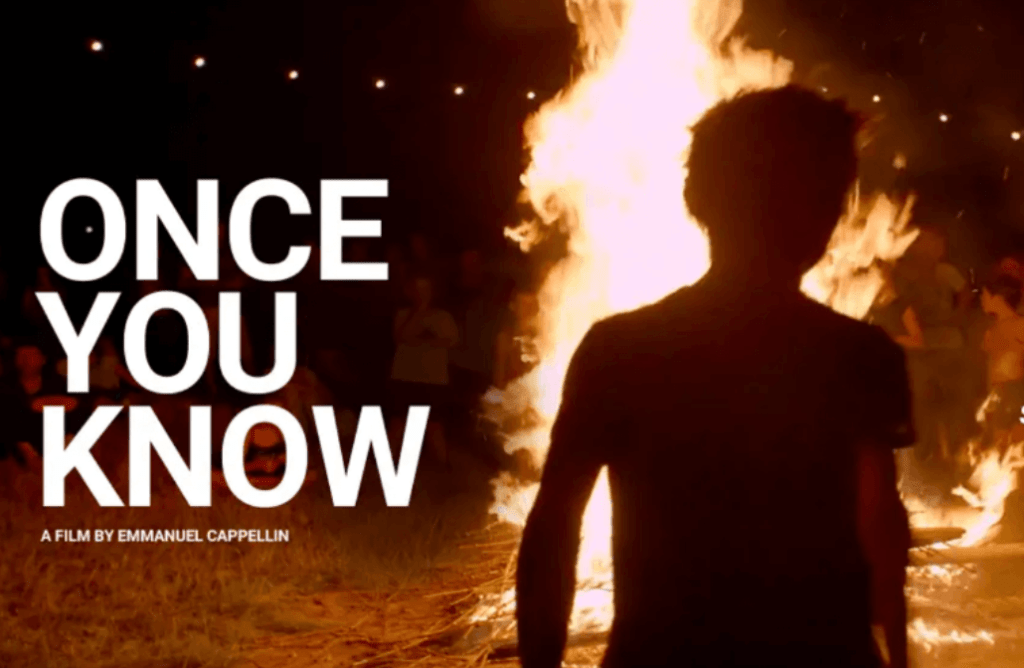

Once You Know. I must have watched Emmanuelle Cappelin’s 2022 rumination on modernity’s explosive ‘great acceleration’ half a dozen times now – sometimes with a roomful of others, sometimes alone. Cappelin sets out from Donnella and David Meadows’ seminal 1972 analysis of ecological overshoot and its implications, Limits to Growth, trying to get his head and his heart around what’s happened since. As his journey into the implications of runaway omnicide begins we hear from a now much older David Meadows, speaking in 2012:

Forty years ago I stood up and presented a question. How can global society organise itself to provide a just, peaceable, equitable, decent living for its people? Forty years ago it was still theoretically possible to slow things down, and come to an equilibrium. Now that’s no longer possible. It means that we are now coming into a period of uncontrolled decline.

Cappelin’s often anguished personal testimony wrestles with what it might mean to walk together into ‘a period of uncontrolled decline’ with our eyes and our hearts open. His film borrows its title from a remark made by Post Carbon Institute founder Richard Heinberg, who’s gentle, rigorous melancholy is central to the film. Once you know what’s happening here, Heinberg tells the much younger Cappelin, there’s no going back to how you were.

So here’s where this starts. With being unable to go back to making art as if making art mattered. Even whilst knowing – of course – that it does. More than ever. This isn’t about taking a position. It’s about being stuck, and needing to begin again. It’s about learning what coming unstuck would mean.

Leave a comment